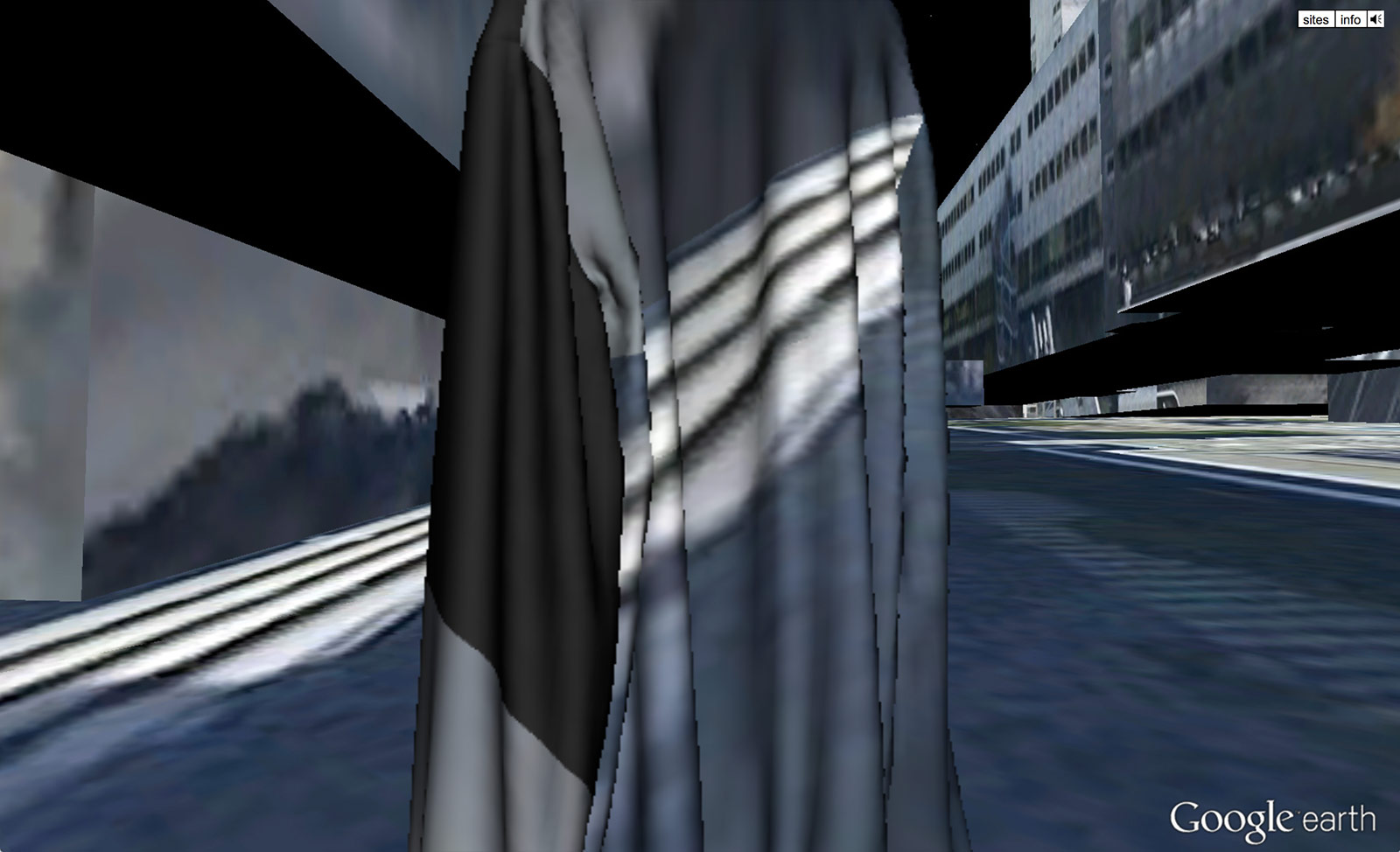

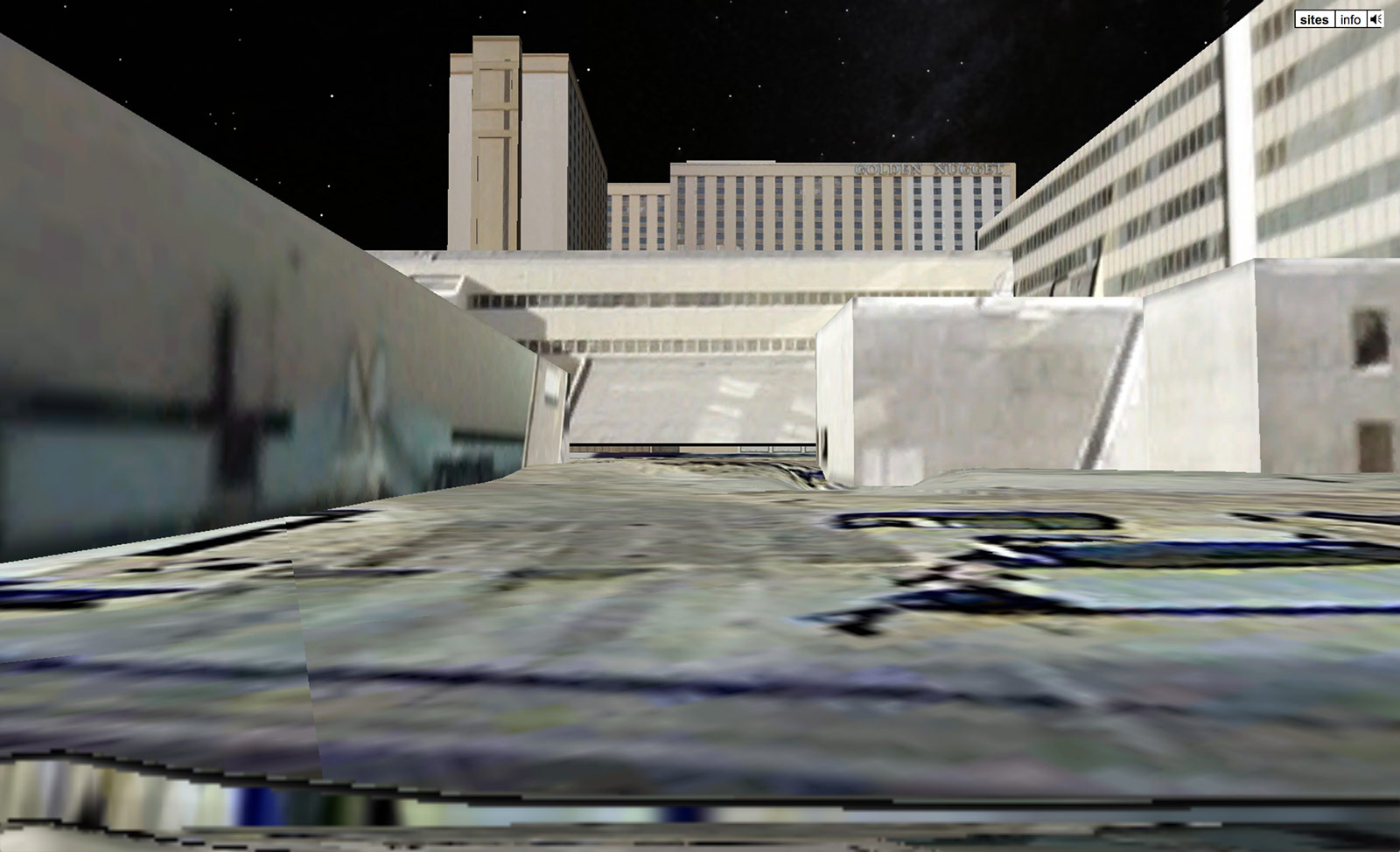

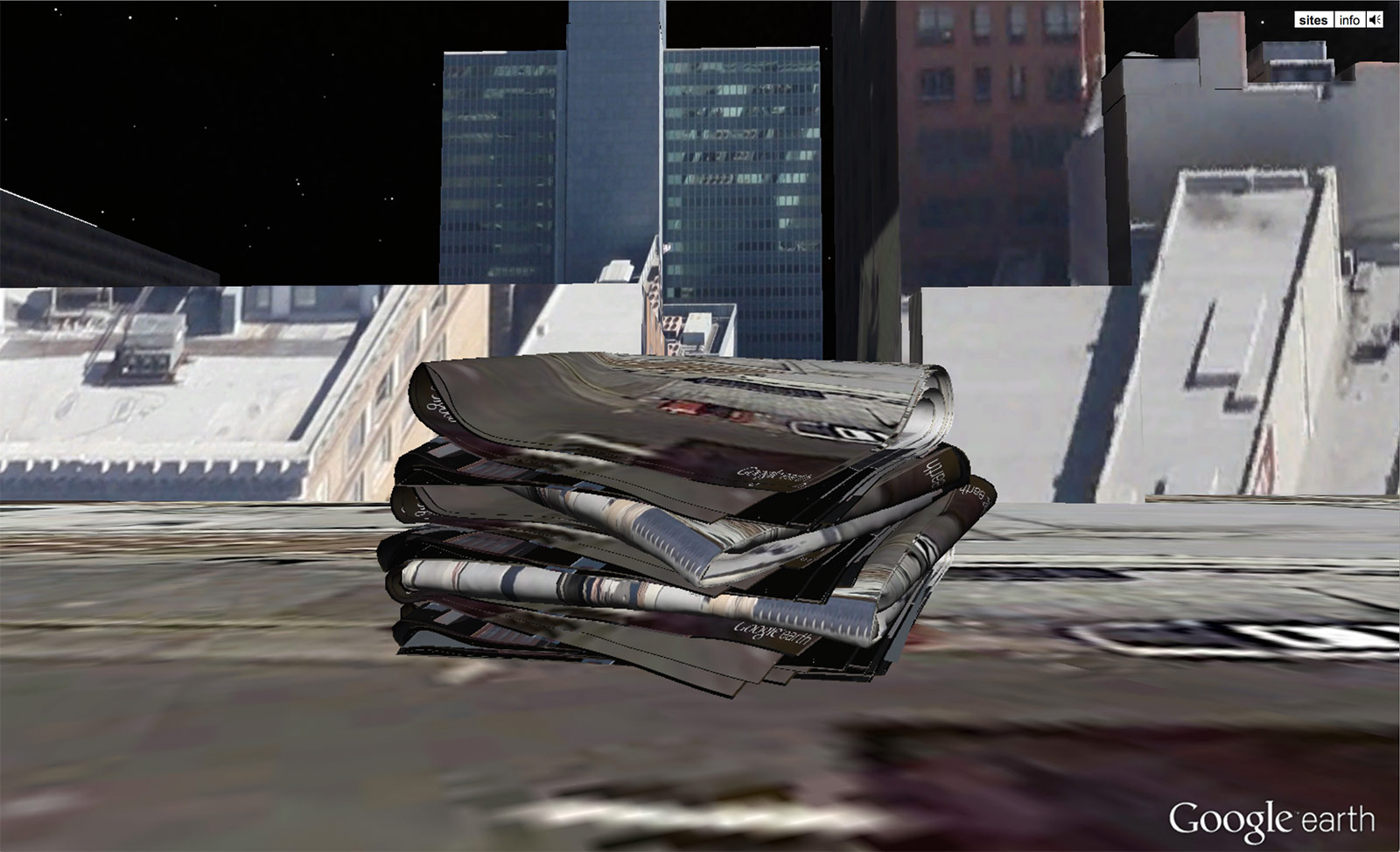

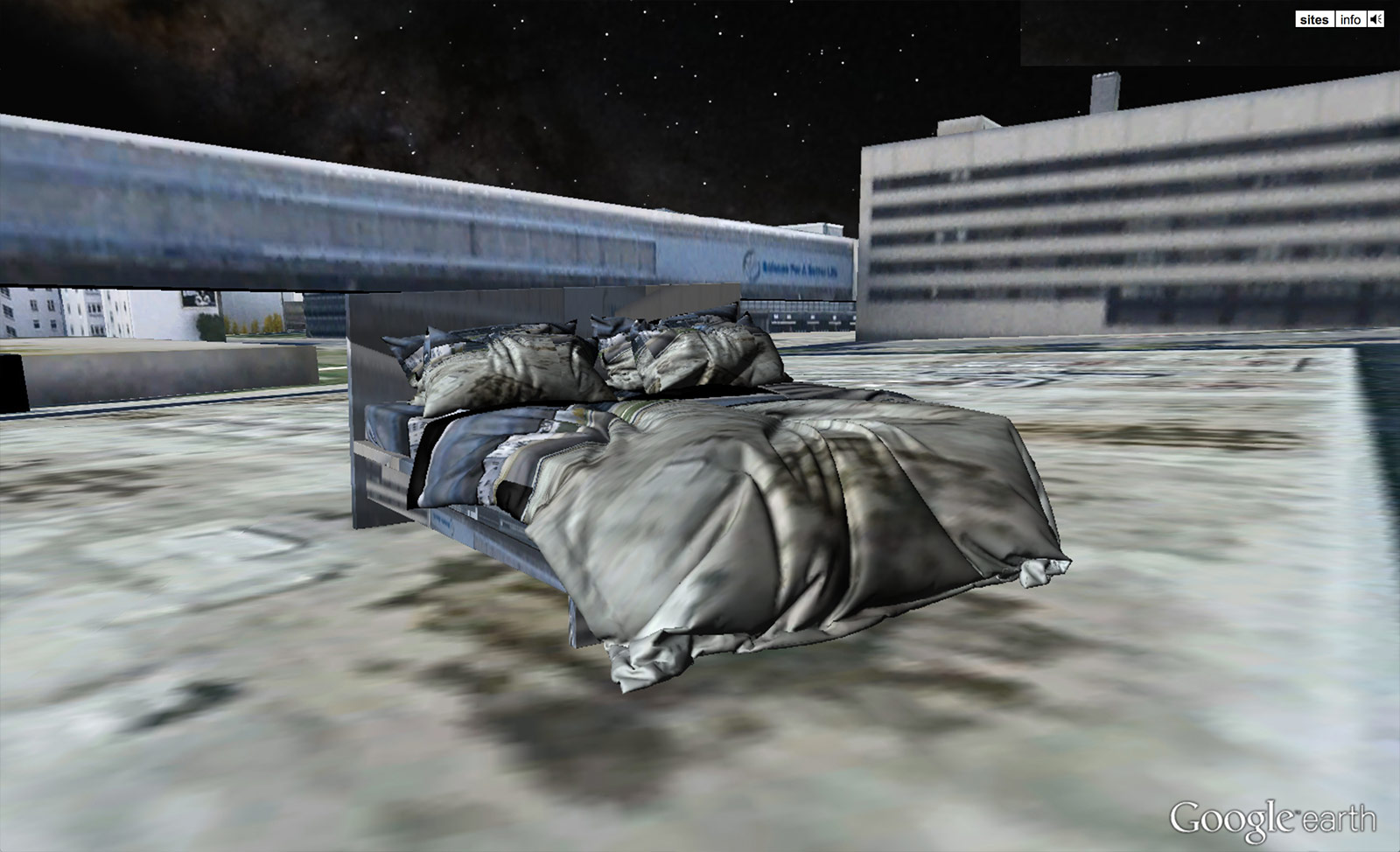

Screenshot, Sites N°5

Screenshot, Sites N°5

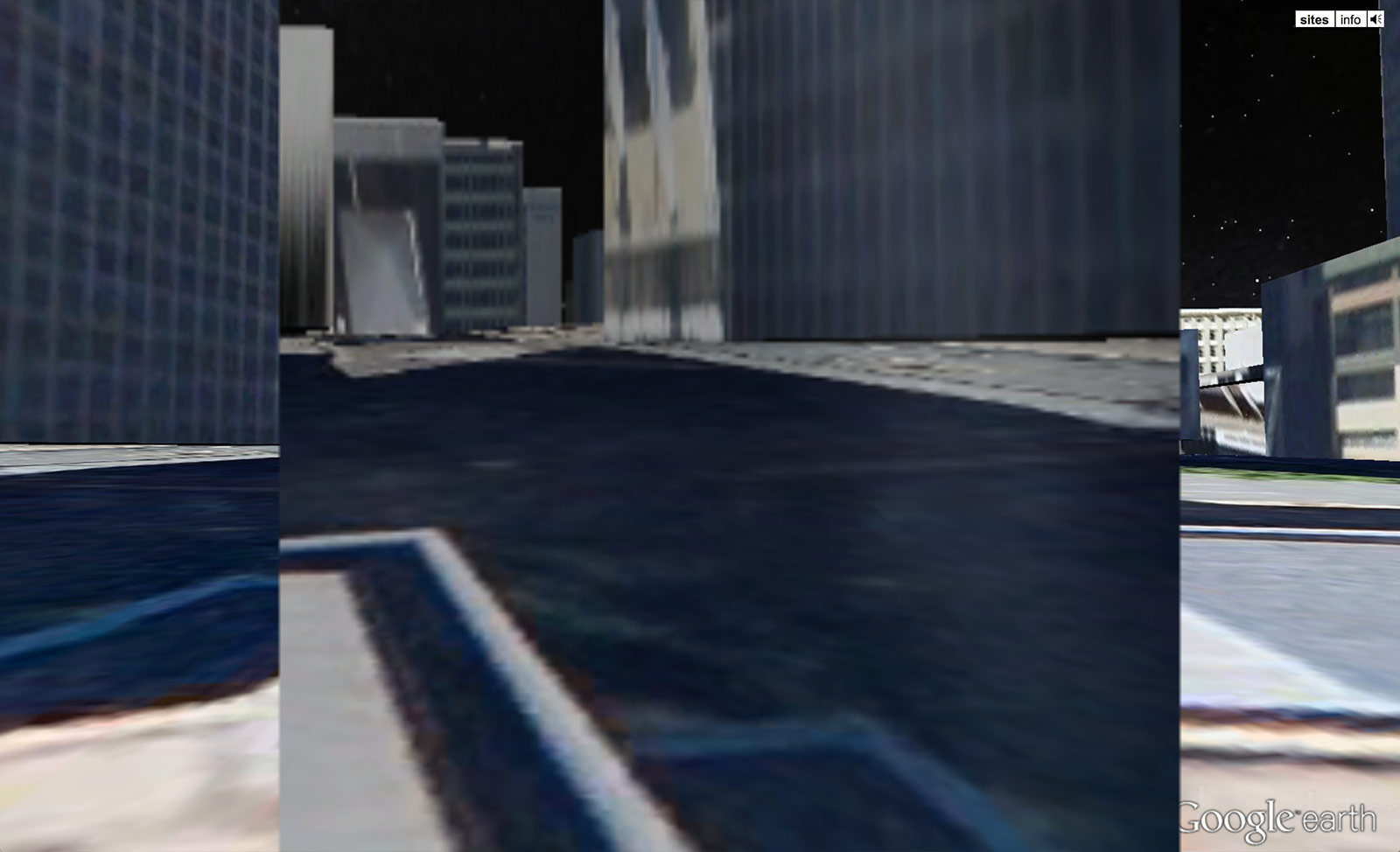

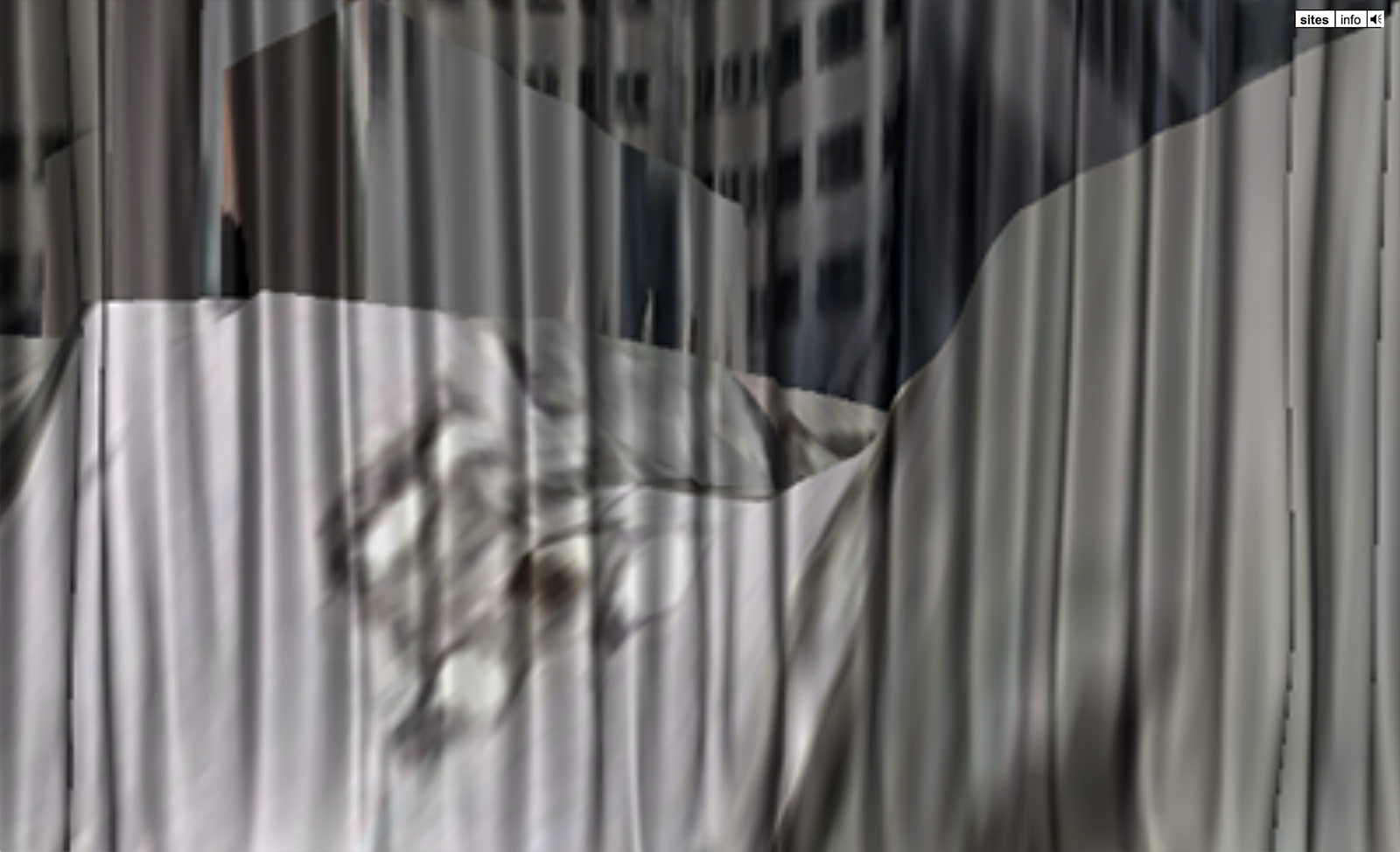

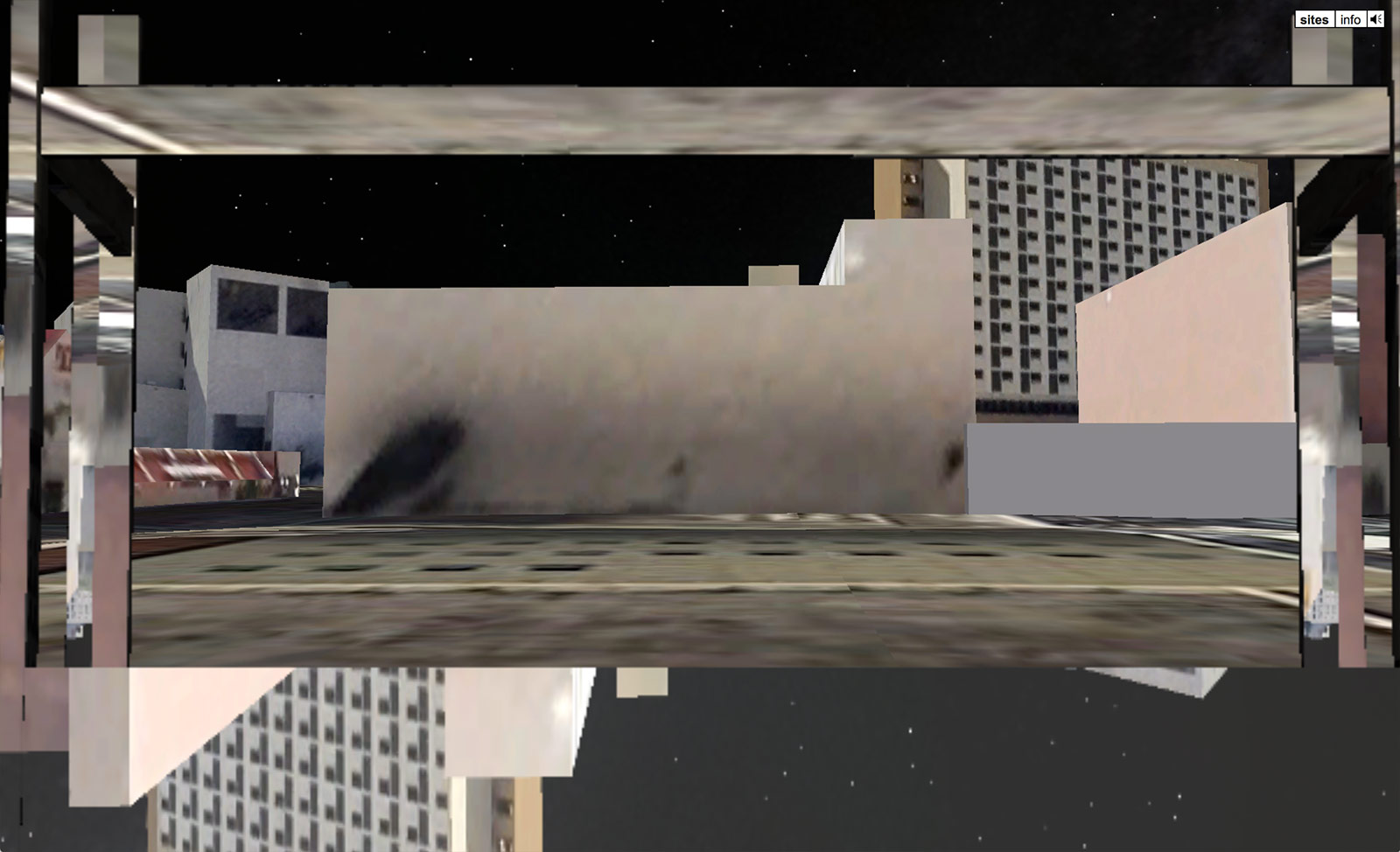

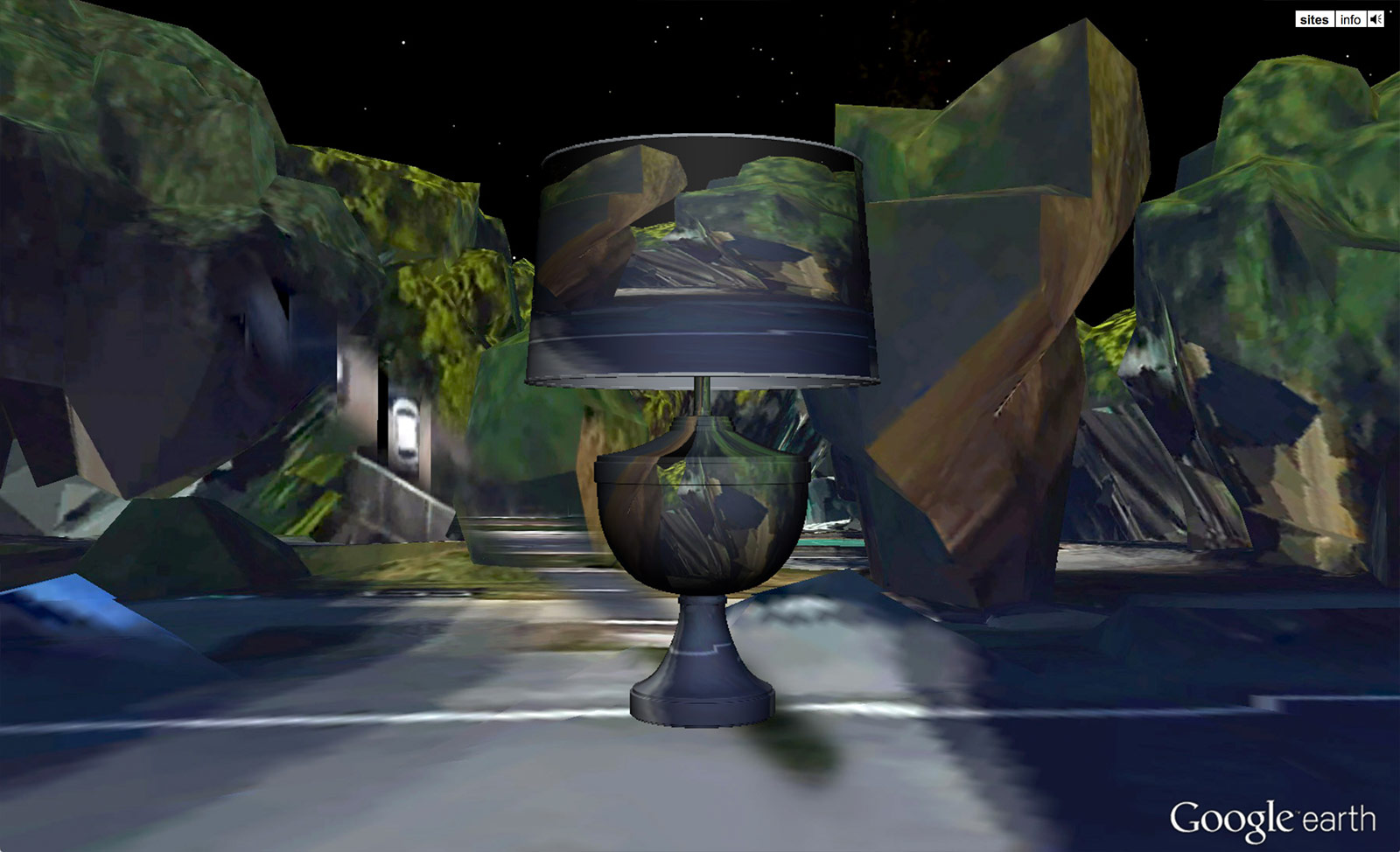

Screenshot, Sites N°7

Screenshot, Sites N°7

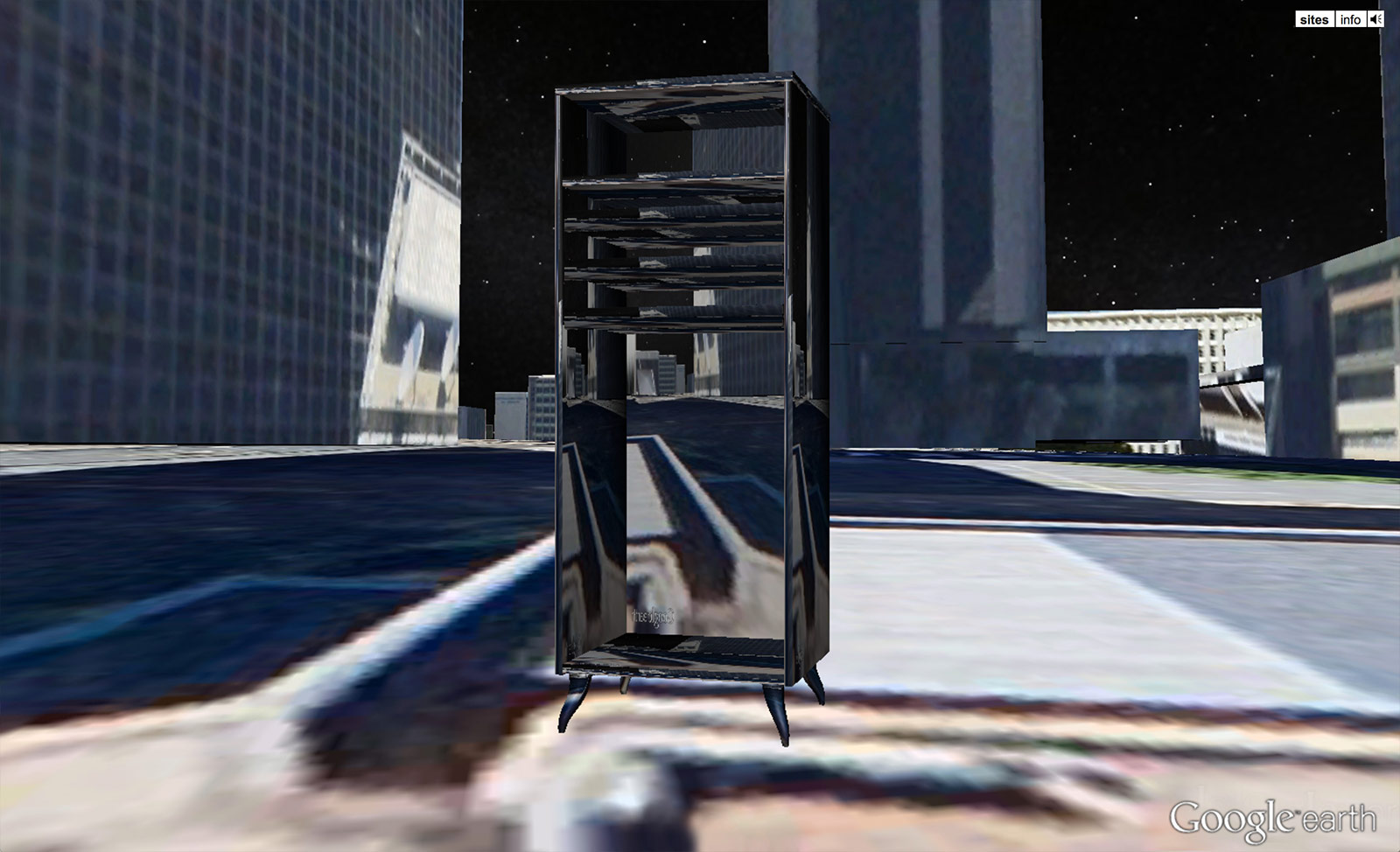

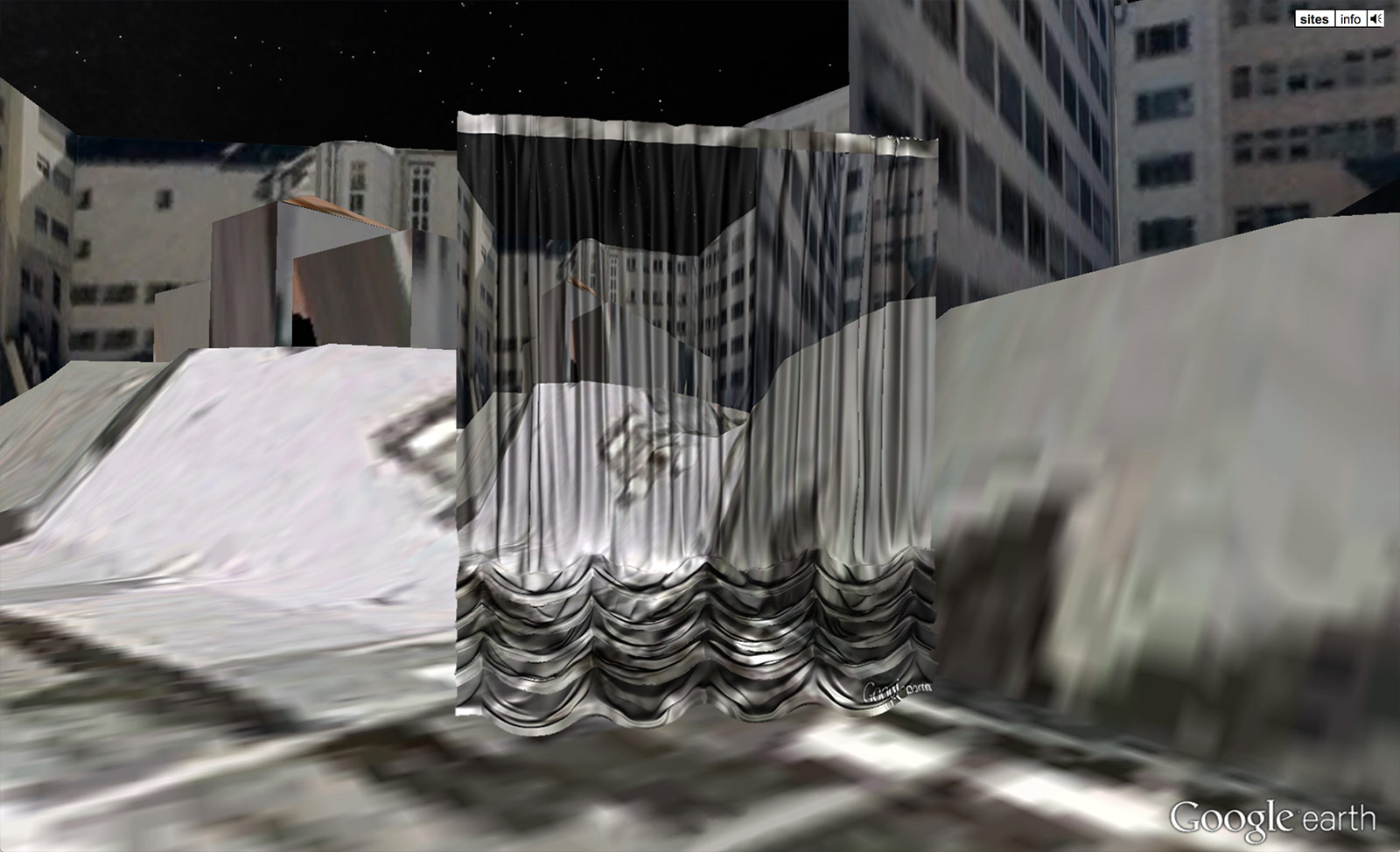

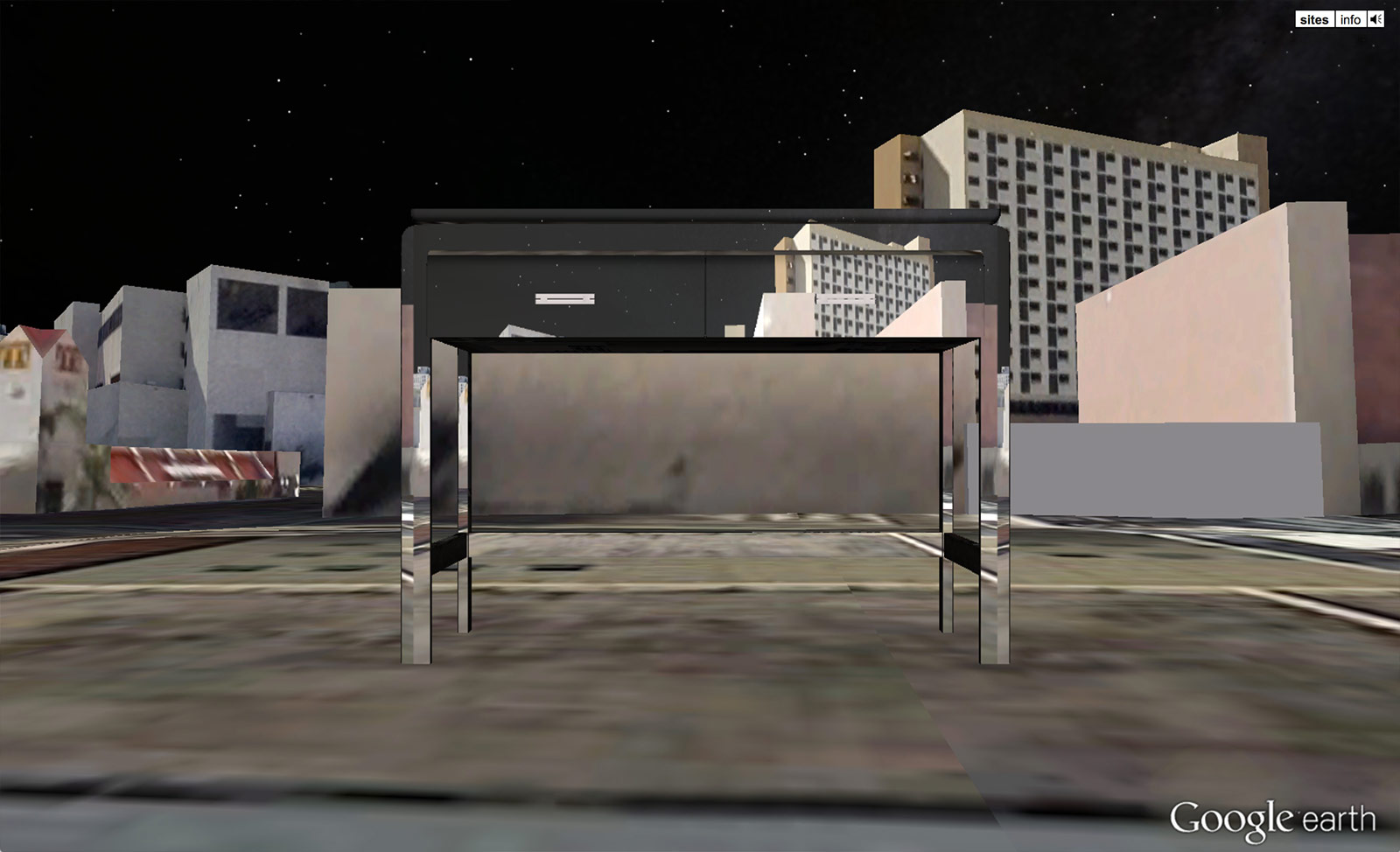

Screenshot, Sites N°8

Screenshot, Sites N°8

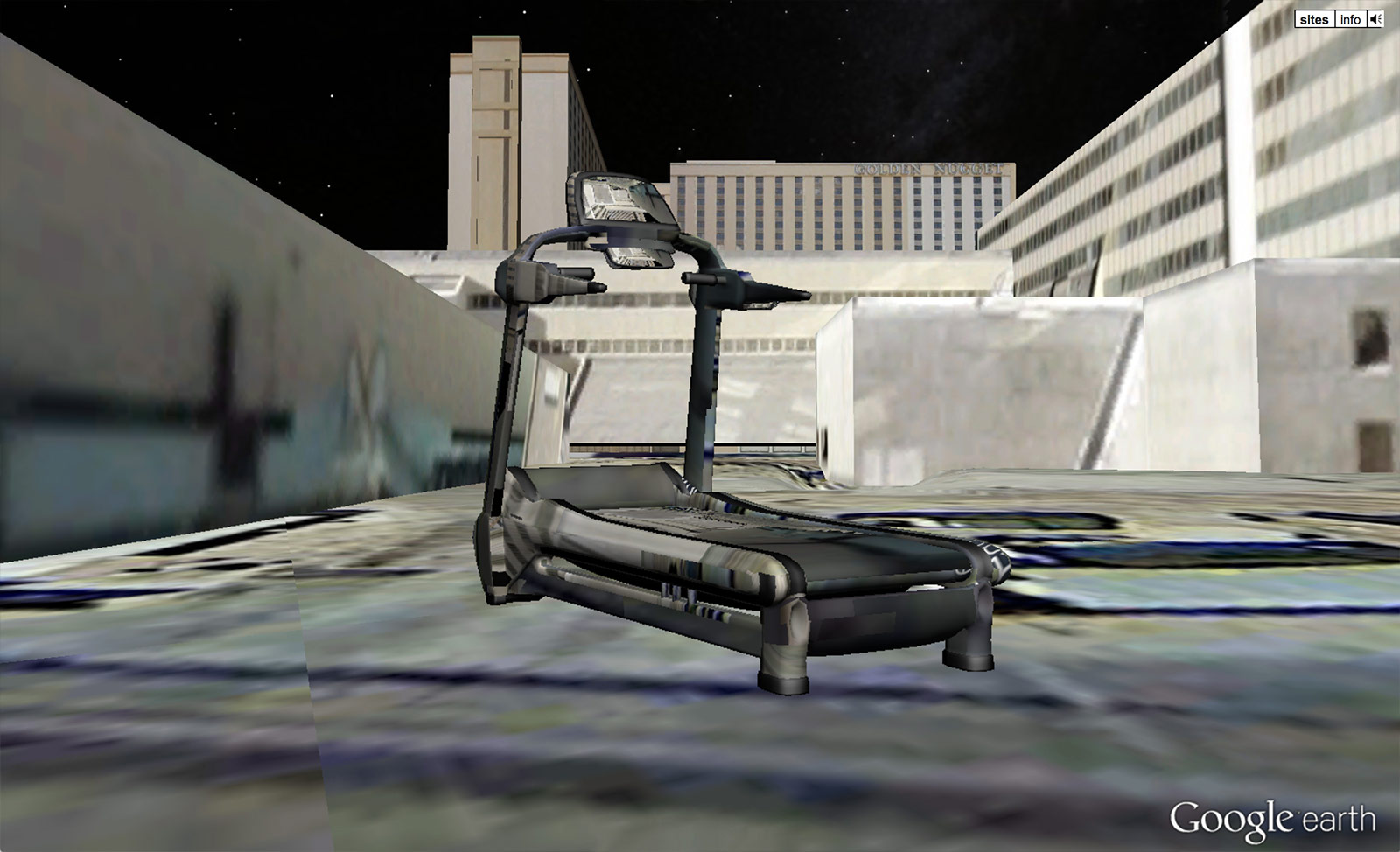

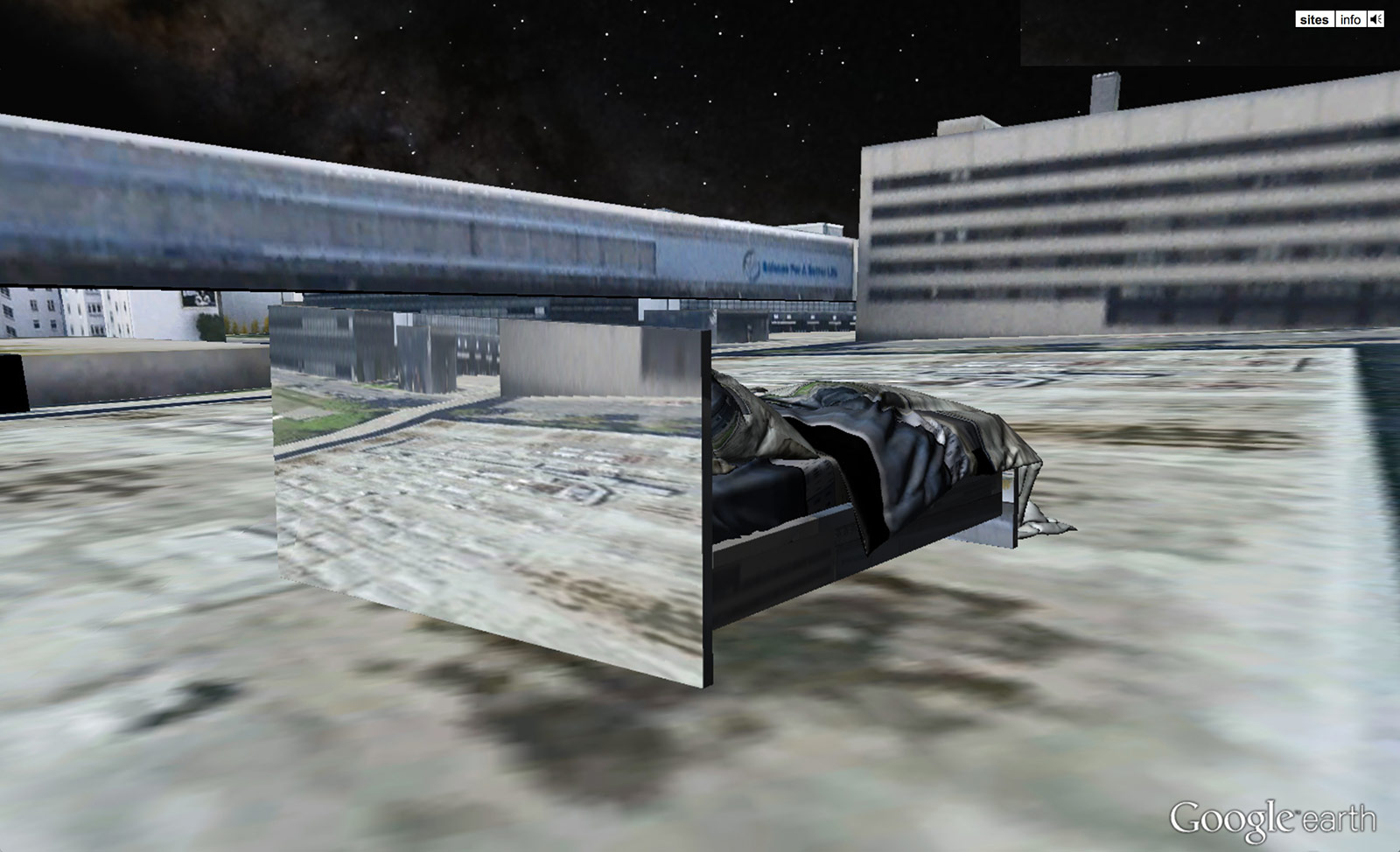

Screenshot, Sites N°3

Screenshot, Sites N°3

Screenshot, Sites N°11

Screenshot, Sites N°11

Screenshot, Sites N°2

Screenshot, Sites N°2

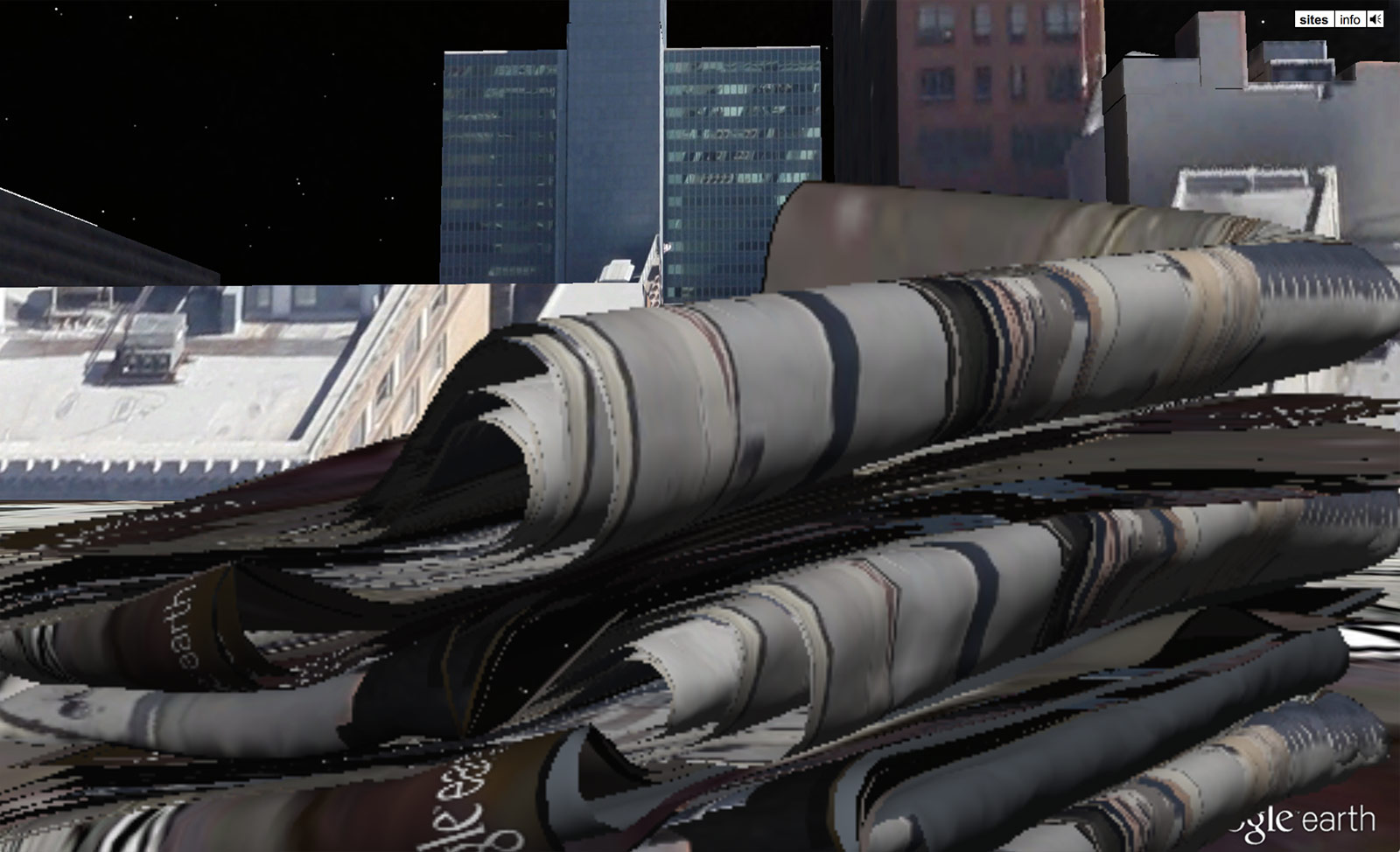

Screenshot, Sites N°10

Screenshot, Sites N°10

Screenshot, Sites N°9

Screenshot, Sites N°9

EN)

«Google Earth is a virtual globe, map and geographical information program that was originally called EarthViewer 3D created by Keyhole, Inc, a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) funded company acquired by Google in 2004. It maps the Earth by the superimposition of images obtained from satellite imagery, aerial photography and geographic information system (GIS) 3D globe.» – en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Earth

Most buildings on Google Earth are auto-generated 3D mashups where flat 2D aerial imagery are streched across the surface of 3D models. This automated process of texture mapping builds a new strange world full of crippled architecture and surreal sceneries.

The work Sites places new 3D models into the world of Google Earth; everyday personal objects from the interior are moved onto empty sites around the world of the Google cartography. These foreign objects are wrapped within the background surrounding them. It is a superimposition of the superimposition, a mashup of the mashup, creating new maps where you navigate through the tiny world of objects like a bed, a chair, a stack of newspapers, a jacket etc. rather than through the wide world of Google earth.

«The work of Esther Hunziker places the people at the interesting point of synthesis between the real-real and the new real. A synthesis that is intended to suppurate old epistemological prejudices against this real we have now been working on for a short century.

Hunziker’s work points to the fact that by building upon these simple lower-level operations we can learn to perform much more ambitious ones: searching for a new understanding of objects, detecting qualities that the digital does or does not share with the real, better synthesizing the way we produce new settings every day, new circumstances to interact with these millions of digital items. The web is a complete modular system, it is composed of innumerous modules, webs, and multiple elements. We are just at the beginning of learning how this architecture is hosting us and not the other way around.»

– myartguides.com/exhibitions/esther-hunziker-sites

Esther Hunziker

– Sites

Text by Chus Martínez

institut-kunst.ch/der-tank/the-commissions/esther-hunziker

I have no idea what media art is. I actually do not think that there is a need to say how the image is produced as long as it works. However, the challenge lies in the display, in the fact that traditional ways of showing art do not really know how to deal with the often ugly or too-specific machines on which “media art” needs to be viewed. Yet there has also been the enormous and stubbornly insistent claim, repeated again and again, that traditional exhibition language is not appropriate for it. I do believe in merging though, and this is the reason why—after a team talk—we saw the possibility of having a double-life in exhibition making: a TANK that is a site where projects and works conceived for the Internet are presented, and a TANK that hosts materials and experiments that are physical in a more traditional understanding of the notion.

It is precisely this debate on how to present digitally conceived works that has always interested Esther Hunziker. Her work shows a rare interest in image phenomena that are genuinely part of our Internet culture.

I was talking to a friend the other day. She said she never goes into a shop at all. She buys all she needs online. It surprised her that I never bought a thing online, apart from a few books. She could not believe it. She sent me a few links, thinking that it was perhaps a lack of knowledge that prevented me from it. I started looking through them one night. After-all, why not? At least to see what people like about it so much. It took me some time to understand that the problem is that all those clothes are kind of floating free in a white background. They are sometimes feared by bodies but they do not really have an expression. Moreover, they are completely dispossessed of a reason, a scenery. Somehow, I thought, as a consumer I am dependent on a “disporama,” on the invention of a situation that then provokes a reason to dress. But the most beautiful part of this research was, undeniably, the zooming in on the textiles. You could use the function to touch with your eyes the texture of clothes. I thought of Google Earth. I used to “go” to my favorite beach on Google Earth just to see how much it changes over time. Or, better said, I checked to see how regularly they update the picture. I was always annoyed that this particular part of Spanish geography was “portrayed” in winter, and not in summer, when it is really beautiful. Zooming in on the territory, you could, like with the clothes, get closer; you could walk on the sand and see if it were even possible to go into the water.

That beach is a complete different thing on Google Earth than it is in my memory, but I can relate to it. With clothes, however, it is different, since the digital memory created by online “touching” may not match the texture of the fabric at home. I thought of Tinder. I also wondered how long it would take not only to see the pictures but to allow the users to come closer, or—similar to how Esther Hunziker operates in her new work—to be able to turn the people around, to simulate some sort of volumetric presence that might help you to make a decision.

All these new functions are tools, and, like every tool, they do not only serve a purpose, they entirely modify the way we see the real. It is also interesting that at the core of the multi-touch screen—and all these functions that play with the idea of our eyes being hands, or forces capable of moving, turning, or affecting objects living in the digital substance—there is an artist: Myron Krueger. He started as early as 1975 to develop his Videoplace, an artificial-reality laboratory that could not only surround users but also respond to them. At the time, the environment was incredibly complex, filming, projecting, and producing a series of sensor-like devices that are at the core of our actual new shopping and coupling experiences.

The work of Esther Hunziker places us exactly at a point where we can reflect upon all these new ways of acting upon the real. Her work makes us attentive to the fact that we are at a strange but interesting point of synthesis between the real-real and the new real. A synthesis that is intended to suppurate old epistemological prejudices against this real we have now been working on for a short century. It is true, for a long time these two trajectories—the real-real and the new real— ran in parallel without crossing paths. But now they have come closer together. We are morphing in ways still undiscovered, ways that offer much more than what they “take” from our former real.

Hunziker’s work points to the fact that by building upon these simple lower-level operations we can learn to perform much more ambitious ones: searching for a new understanding of objects, detecting qualities that the digital does or does not share with the real, better synthesizing the way we produce new settings every day, new circumstances to interact with these millions of digital items. The web is a complete modular system, it is composed of innumerous modules, webs, and multiple elements. We are just at the beginning of learning how this architecture is hosting us and not the other way around.